Tsa Tsa Project

“Actually, you create even more merit by making the images in the water than in clay. This water, which you’ve just blessed by stamping an image of the Buddhas in it, flows on for miles and miles, joining streams and rivers and eventually flowing into the ocean. Every sentient being that tastes or touches this water is blessed by it: all the water becomes blessed. And you can imagine how many sentient beings there are in the ocean. In fact, you think about it, the vast majority of all living beings on this planet live in the ocean, so what a wonderful way to benefit them.” – Geshe Lama Konchog

In June 2015, under the guidance of Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s sister Ven. Ngawang Samten, the Bodhichitta Trust sponsored FPMT nun Ven. Katy Cole and Kopan monk Ven. Jikme to make 700,000 water tsa-tsas – tsa-tsas made by “stamping” the moulds of holy images onto water – at the Gyachog River at Khisa Bhu, a holy place in the Solu Khumbu region of the Nepalese Himalayas (about a 45-minute down-hill trek from Lawudo Gompa, Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s family’s home).

In 2004 Rinpoche advised Ven. Robina to make 700,000 tsa-tsas: 350,000 of Buddha Mitrugpa, and 350,000 of Lama Tsong Khapa. Making tsa-tsas is one of the traditional preliminary practices in the Gelug tradition, and a powerful one, according to the lamas. Rinpoche says:

“Making more than five tsa-tsas has inexpressible benefits. Even in this life, you will have less disease, your enjoyments will increase, and you will achieve long life and good reputation. It is the best method to betray death. Making tsa-tsas pacifies obstacles, bad conditions, accidents, and sudden diseases like heart attacks and paralysis. By making tsa-tsas you pacify enemies, interferers, and harms. You accumulate all merit, purify all obscurations, and achieve the resultant three kayas in future life. The benefits of making tsa-tsas are inexpressible; the telling of all the details can never be finished.”

In the conventional tsa-tsa making method, a practitioner would use the moulds of holy images to create small clay or plaster low-relief images of buddhas or stupas. It can be an expensive, laborious, and messy process, requiring mixing the clay or plaster, incorporating various prayers and blessed substances, setting the moulds, making sure there are no bubbles or breaks, painting the dried tsa-tsas, figuring out how and where to store them properly, etc. And like Ven. Robina, practitioners are often given huge numbers to complete.

Water tsa-tsas can be easily completed by comparison, but can only be done in a very pure, holy place where the water is completely unpolluted and untouched by human or industrial pollution. Kisa Bu, about half a mile (800 meters) trek from Lawudo Gompa is such a place.

Lawudo Gompa, or “Magnificent Cave of Attainments,” is where Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s previous incarnation, the great Nyingmapa lama Kunsang Keshe, the Lawudo Lama, spent the last 20 years of his life, in deep retreat. Since 1970 Lawudo has been the home of Rinpoche’s family. Rinpoche’s sister, Ven. Ngawang Samten, who is 78, runs the center, including all the cooking and caring for the gompa, and looking after the center’s farms and cows.

Between 2004, when Rinpoche first advised Ven. Robina to make the 700,000 tsa-tsas, and June 2015, over 230,000 tsa-tsas were offered towards Ven. Robina’s commitment. Ven. Katy organized the majority to be made by nunneries in Nepal, and also made tsa-tsas herself. Ven. Aileen Barry, Victoria Rainone, and Sarah Brooks also all offered tsa-tsas towards Ven. Robina’s commitment.

In June 2015 Rinpoche asked Ven. Katy to go to Lawudo to help Ven. Samten with the day-to-day running of the center after the devastating April earthquakes that hit Nepal. Ven. Samten and others in the Lawudo area were living in tents as the majority of the mud and brick buildings in the area had been damaged. The day-to-day work of running the center had doubled under the difficult conditions.

It was Ven. Samten who suggested making water tsa-tsas to Ven. Katy. A much more practical, less expensive means of completing the commitment, Ven. Samten said, but could only be done in a very pure place like Kisa Bu.

The Solu Khumbu, in general, is a very special, blessed environment. The region is charged with some 400 years of Buddhist practice, devotion and blessings: by the collective karma of the Sherpas living there, practicing Buddhist morality – the lamas say the root cause to experience purity or pollution is determined by one’s inner environment; by the environment itself which is a landscape of holy objects; and by the blessings of the innumerable practitioners and yogis who’ve meditated there.

The Solu Khumbu lacks much of the environmental and karmic pollution we experience in cities, and in the Western world, in general. Sherpas, like Tibetans, with whom they share ancestry, are Buddhist and so follow the precept of “no killing.” Not only are animals in the region rarely killed for food or hunted, but all life is respected, including the lives of insects and rodents. Much of the day-to-day killing and violence we accept as part of every day life in the West doesn’t occur: there are no exterminators, no animals and insects killed in mass food production, no pesticides used to kill bugs on crops, not even any cars – people travel from village to village either by walking up and down the steep mountain paths, or on horseback.

The outer environment of the Solu Khumbu is also charged with the power of holy objects. Everywhere rocks and boulders have mantras and holy images carved and painted on them. You see stupas, prayer wheels, and prayer flags throughout the landscape, blessing the land and all the beings of the earth and sky. All beings – human, animal, etc – that see, or are touched by winds that have blown across these holy objects – are constantly receiving the blessing of those deities and holy images.

The entire region is also embued with the blessings of the great yogis and practitioners who have meditated and attained realizations in the region for hundreds of years. It’s also a sacred place of Padhmasambava, or Guru Rinpoche, an 8th century bodhisattva who is said to have left termas, or sacred texts, hidden throughout the region. In fact, the entire Solu Khumbu region is considered to be a beyul, or a hidden Buddhist pure land blessed by Guru Rinpoche.

So great is the devotion of the local people that there are even self-emanations: images of Buddhas that seemingly “self-arise” from rocks and cliffs – these rock statues are not man-made! But actually are growing, seemingly of their own accord, from rocks, cliffs and in caves.

So it is an incredibly blessed, pure environment.

“I had never heard of water tsa-tsas,” Ven. Katy said. “Ven. Samten explained they are sometimes done at this very holy place on the Gyachog River: Kisa Bu. She suggested do them with the help of Ven. Jikme, whose mother had recently died in the first earthquake.”

At Kisa Bu the snow melt from Khubu Yu La Mountain, or “Goddess of the Kumbu Mountain,” and water from Gyachog mountain lake meet and flow down into the Gyachog River. The locals regard Khubu Yu La Moutain as holy, and the water that runs from it as nectar. “They will often will bless themselves with it at Tesho, a village further down the mountain, and offer katags to the water by tying them to the railings of the bridge,” Ven. Katy said.

There’s no human activity at all that affects the river before it reaches Kisa Bu – no washing, or any human contamination that could pollute the water, so Kisa Bu is the perfect environment in which one can do the water tsa-tsa practice: stamping the tsa-tsas onto “pure, clean nectar,” Ven. Katy said. “Ven. Samten explained we would further bless the water with the tsa-tsa practice, so many animals and so many insects will benefit. ‘Very good!’ she said.”

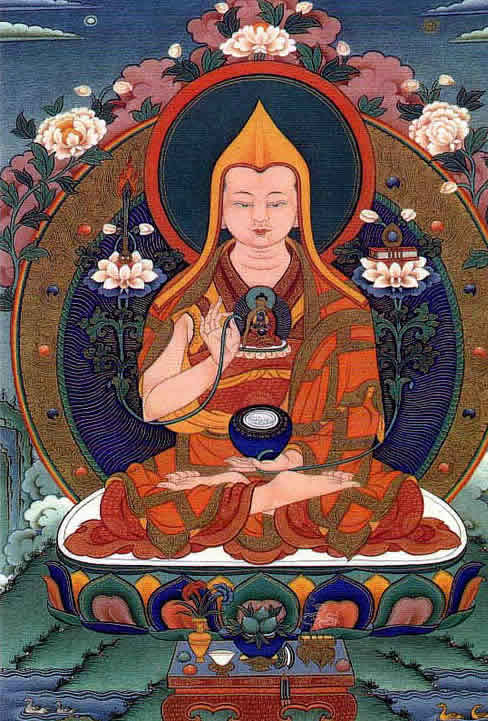

The nuns of Thame gompa loaned Ven. Katy and Ven. Jikme the molds: one of Lama Tsong Khapa, the 14th century patron saint of the Gelug lineage (which also had Atisha, the great 11th century Buddhist philosopher and yogi, and Namgyalma, a long-life deity); and a Migtrupa Buddha, a powerful Buddha of purification. It took them three weeks to complete the 700,000.

It would take Ven. Katy about 45 minutes to walk down to Kisa Bu each morning from Lawudo, and about 1.5 hours to walk back at the end of the day. “It was an incredibly difficult trek each day at that elevation!” she said. “The path is rough and the air is so think. I would have to stop and take breaks along the way.”

“The first day, I thought I might not be strong enough to make it there and back every day. Ven. Jikme skipped down the slippery, uneven, rocky trail, bush bashing as he went. I could barely see the path! If he had left me alone, I would have been lost. My legs were shaking, trying to keep up, and I was nearly in tears thinking it was not going to be possible for me to go up and down each day. But I got stronger each day.”

As soon as they reached the river on the first day, June 12, an auspicious day in the Tibetan calendar, Ven. Jikme and Ven. Katy did a puja to request permission from the local spirits to do the tsa-tsa practice there and then got to work. Ven. Samten advised them how to do the practice:

“Ven. Samten said we should count the number of times we stamped the tsa-tsas on to the water, and simultaneously recite continuously the mantra of the deity we were working with. At the same time we were to visualize many thousands of the Buddhas floating down the river blessing everything in their path.” Ven. Katy also used Rinpoche’s teachings on how to make tsa tsa’s and how to visualize while making them.

Soon they were making 25,000 tsa-tsa’s a day. “We were doing in three weeks, double the number we had struggled so hard to do over the past 11 years,” Ven. Katy said. “I was so happy that the conditions that had arisen for us to do this practice.”

Ven. Samten organized for Ven. Katy and Ven. Jikme to have lunch every day with Dawa and Lakma Sherpa, the one family living at Kisa Bu. They are farmers and Dawa was one of the early Kopan monks. His family is related to the previous Lawudo Lama. Dawa left Kopan to become a climbing porter, and worked many years for Russell Brice’s company HIMEX. He summited Everest four times. Now his son works for the same company.

A few days into the practice the weather turned; it started to rain and the monsoon winds started blowing. “I thought we would not be able to complete the commitment, as the monsoon was setting in, but somehow, we managed to finish our daily 25,000 by 1:30pm that day, and get back to Lawudo before the rain started. There were only two days I did not go down due to weather, and very few days where I was caught in the rain.”

“Jigme finished his 350,000 two days before me. As my commitment came to a close, I felt both a sense of relief at not having to climb that hill again, and also some nostalgia as I knew I would probably never have such an amazing opportunity to do such a practice, in such pristine, perfect, idyllic conditions again. I felt as if I had been allowed into a secret Shangri La where everything was perfect and easy to achieve. And to have had advice and guidance from such an incredible, humble practitioner as Ven. Samten, who professes to only know about cows... I feel so honored to have had the opportunity to have done this practice. I pray these tsa tsa's will remove any obstacles to Ven. Robina’s life and projects, and Sherab Plaza and the Bodhichitta Trust to be able to serve sentient beings exactly according to Ven. Robina’s wishes.”

Irish nun Ven. Aileen Barry, who ran Liberation Prison Project's Australian office for five years and is now based at Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo's nunnery in Dharamsala, offered nearly 2,000 Lama Tsong Khapa tsa-tsas towards Ven. Robina's commitment. Photo Ven. Aileen Barry.

Lama Tsong Khapa, (1357-1419), founder of the Gelugpa school of Tibetan Buddhism.

Sarah Brooks helping fill the stupa at FPMT's Kadampa center with the 2,000 Mitrugpa tsa-tsas she offered Ven. Robina in 2012 (above); and a look inside the stupa at the tsa-tsas, wrapped in yellow paper (below). "I offer these to Ven. Robina with all my heart," Sarah said. Photos Sarah Brooks.

Mitrugpa, or Akshobya, one of the five Dhyani Buddhas. Thangka by Jampa Tsondue.

Ven. Katy making tsa-tsas during her 2008 retreat at the FPMT retreat center in South Australia. Photo Ven. Katy Cole.